Schwarzschild metric

| General relativity |

|---|

| Introduction Mathematical formulation Resources |

|

Fundamental concepts

|

|

Phenomena

|

|

Advanced theories

|

|

Schwarzschild

Reissner–Nordström · Gödel Kerr · Kerr–Newman Kasner · Taub-NUT · Milne · Robertson–Walker pp-wave · van Stockum dust |

In Einstein's theory of general relativity, the Schwarzschild solution (or the Schwarzschild vacuum), named after Karl Schwarzschild, describes the gravitational field outside a spherical, uncharged, non-rotating mass such as a (non-rotating) star, planet, or black hole. It is also a good approximation to the gravitational field of a slowly rotating body like the Earth or Sun. The cosmological constant is assumed to equal zero.

According to Birkhoff's theorem, the Schwarzschild solution is the most general spherically symmetric, vacuum solution of the Einstein field equations. A Schwarzschild black hole or static black hole is a black hole that has no charge or angular momentum. A Schwarzschild black hole has a Schwarzschild metric, and cannot be distinguished from any other Schwarzschild black hole except by its mass.

The Schwarzschild black hole is characterized by a surrounding spherical surface, called the event horizon, which is situated at the Schwarzschild radius, often called the radius of a black hole. Any non-rotating and non-charged mass that is smaller than its Schwarzschild radius forms a black hole. The solution of the Einstein field equations is valid for any mass M, so in principle (according to general relativity theory) a Schwarzschild black hole of any mass could exist if conditions became sufficiently favorable to allow for its formation.

Contents |

History

The Schwarzschild solution is named in honor of Karl Schwarzschild, who found the exact solution in 1915,[1] only about a month after the publication of Einstein's theory of general relativity.[2] It was the first exact solution of the Einstein field equations other than the trivial flat space solution. Schwarzschild had little time to think about his solution. He died shortly after his paper was published, as a result of a disease he contracted while serving in the German army during World War I.[3]

Johannes Droste in 1915[4] independently produced the same solution as Schwarzschild, using a simpler more direct derivation.[5]

In the early years of general relativity there was a lot of confusion about the nature of the singularities found in the Schwarzschild and other solutions of the Einstein field equations. In his 1916 paper[1] Schwarzschild took the position that the singularity at r = rs should be identified with the coordinate singularity at the origin present in spherical coordinates on flat space. A more complete analysis of the singularity structure was given by David Hilbert in the following year, identifying the singularities both at r = 0 and r = rs. Although there was general consent that the singularity at r = 0 was 'genuine' physical singularity, the nature of the singularity at r = rs remained unclear. In 1924 Arthur Eddington produced the first coordinate transformation (Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates) that showed that the singularity at r = rs was a coordinate artifact, although he seems to have been unaware of the significance of this discovery. Later, in 1932, Georges Lemaître gave a different coordinate transformation (Lemaître coordinates) to the same effect and was the first to recognize that this implied that the singularity at r = rs was not physical. In 1939 Howard Robertson showed that a free falling observer descending in the Scwharzschild metric would cross the r = rs singularity in a finite amount of proper time even though this would take an infinite amount of time in terms of coordinate time t.[6]

In 1950, John Synge produced a paper[7] that showed the maximal analytic extension of the Schwarzschild metric, again showing that the singularity at r = rs was a coordinate artifact. This result was later rediscovered by Martin Kruskal,[8] who improved on Synge's result by providing a single set of coordinates that covered (almost) the entire spacetime. However due to the obscurity of the journals in which the papers of Lemaître and Synge were published their conclusions went unnoticed, with many of the major players in the field including Einstein believing that singularity at the Schwarzschild radius was physical.[6]

Progress was only made in the 1960s when the more exact tools of differential geometry entered the field of general relativity allowing more exact definitions of what it means for a Lorentzian manifold to be singular. This lead to definitive identification of the r = rs singularity in the Schwarzschild metric as an event horizon (a hypersurface in spacetime that can only be crossed in one direction).[6]

The Schwarzschild metric

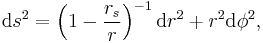

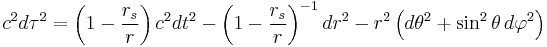

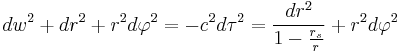

In Schwarzschild coordinates, the Schwarzschild metric has the form:

where:

- τ is the proper time (time measured by a clock moving with the particle) in seconds,

- c is the speed of light in meters per second,

- t is the time coordinate (measured by a stationary clock at infinity) in seconds,

- r is the radial coordinate (circumference of a circle centered on the star divided by 2π) in meters,

- θ is the colatitude (angle from North) in radians,

- φ is the longitude in radians, and

- rs is the Schwarzschild radius (in meters) of the massive body, which is related to its mass M by rs = 2GM/c2, where G is the gravitational constant.[9]

The analogue of this solution in classical Newtonian theory of gravity corresponds to the gravitational field around a point particle.[10]

In practice, the ratio rs/r is almost always extremely small. For example, the Schwarzschild radius rs of the Earth is roughly 8.9 millimeters (0.35 in), while the sun, which is 3.3×105 times as massive[11] has a Schwarzschild radius of approximately 3.0 km (1.9 mi). A satellite in a geosynchronous orbit has a radius r that is roughly four billion times larger than the earth's Schwarzschild radius at 42,164 km (26,199 mi). Even at the surface of the Earth, the corrections to Newtonian gravity are only one part in a billion. The ratio only becomes large close to black holes and other ultra-dense objects such as neutron stars.

The Schwarzschild metric is a solution of Einstein's field equations in empty space, meaning that it is valid only outside the gravitating body. That is, for a spherical body of radius R the solution is valid for r > R. To describe the gravitational field both inside and outside the gravitating body the Schwarzschild solution must be matched with some suitable interior solution at r = R.

When considering an object falling into a black hole, it is better to use a different coordinate system such as Kruskal–Szekeres coordinates.

Singularities and black holes

The Schwarzschild solution appears to have singularities at r = 0 and r = rs; some of the metric components blow up at these radii. Since the Schwarzschild metric is only expected to be valid for radii larger than the radius R of the gravitating body, there is no problem as long as R > rs. For ordinary stars and planets this is always the case. For example, the radius of the Sun is approximately 700,000 km, while its Schwarzschild radius is only 3 km.

The singularity at r = rs divides the Schwarzschild coordinates in two disconnected patches. The outer patch with r > rs is the one that is related to the gravitational fields of stars and planets. The inner patch 0 < r < rs, which contains the singularity at r = 0, is completely separated from the outer patch by the singularity at r = rs. The Schwarzschild coordinates therefore give no physical connection between the two patches, which may be viewed as separate solutions. The singularity at r = rs is an illusion however; it is an instance of what is called a coordinate singularity. As the name implies, the singularity arises from a bad choice of coordinates or coordinate conditions. When changing to a different coordinate system (for example Lemaitre coordinates, Eddington-Finkelstein coordinates, Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates, Novikov coordinates, or Gullstrand–Painlevé coordinates) the metric becomes regular at r = rs and can extended the external patch to values of r smaller than rs. Using a different coordinate transformation one can then relate the extended external patch to the inner patch.[12]

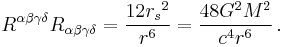

The case r = 0 is different, however. If one asks that the solution be valid for all r one runs into a true physical singularity, or gravitational singularity, at the origin. To see that this is a true singularity one must look at quantities that are independent of the choice of coordinates. One such important quantity is the Kretschmann invariant, which is given by

At r = 0 the curvature blows up (becomes infinite) indicating the presence of a singularity. At this point the metric, and space-time itself, is no longer well-defined. For a long time it was thought that such a solution was non-physical. However, a greater understanding of general relativity led to the realization that such singularities were a generic feature of the theory and not just an exotic special case. Such solutions are now believed to exist and are termed black holes.

The Schwarzschild solution, taken to be valid for all r > 0, is called a Schwarzschild black hole. It is a perfectly valid solution of the Einstein field equations, although it has some rather bizarre properties. For r < rs the Schwarzschild radial coordinate r becomes timelike and the time coordinate t becomes spacelike. A curve at constant r is no longer a possible worldline of a particle or observer, not even if a force is exerted to try to keep it there; this occurs because spacetime has been curved so much that the direction of cause and effect (the particle's future light cone) points into the singularity. The surface r = rs demarcates what is called the event horizon of the black hole. It represents the point past which light can no longer escape the gravitational field. Any physical object whose radius R becomes less than or equal to the Schwarzschild radius will undergo gravitational collapse and become a black hole.

Alternative (isotropic) formulations of the Schwarzschild metric

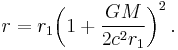

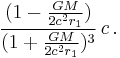

The original form of the Schwarzschild metric involves anisotropic coordinates, in terms of which the velocity of light is not the same for the radial and transverse directions (pointed out by A S Eddington).[13] Eddington gave alternative formulations of the Schwarzschild metric in terms of isotropic coordinates (provided r ≥ 2GM/c2 [14]).

In isotropic spherical coordinates, one uses a different radial coordinate, r1, instead of r. They are related by

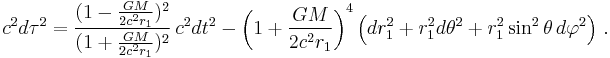

Using r1, the metric is

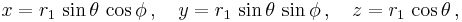

For isotropic rectangular coordinates x, y, z, where

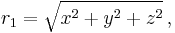

and

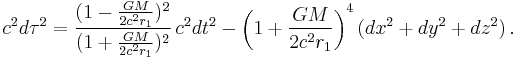

the metric then becomes

In the terms of these coordinates, the velocity of light at any point is the same in all directions, but it varies with radial distance r1 (from the point mass at the origin of coordinates), where it has the value

Flamm's paraboloid

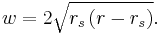

The spatial curvature of the Schwarzschild solution for  can be visualized as the graphic shows. Consider a constant time equatorial slice through the Schwarzschild solution (θ = π/2, t = constant) and let the position of a particle moving in this plane be described with the remaining Schwarzschild coordinates (r, φ). Imagine now that there is an additional Euclidean dimension w, which has no physical reality (it is not part of spacetime). Then replace the (r, φ) plane with a surface dimpled in the w direction according to the equation (Flamm's paraboloid)

can be visualized as the graphic shows. Consider a constant time equatorial slice through the Schwarzschild solution (θ = π/2, t = constant) and let the position of a particle moving in this plane be described with the remaining Schwarzschild coordinates (r, φ). Imagine now that there is an additional Euclidean dimension w, which has no physical reality (it is not part of spacetime). Then replace the (r, φ) plane with a surface dimpled in the w direction according to the equation (Flamm's paraboloid)

This surface has the property that distances measured within it match distances in the Schwarzschild metric, because with the definition of w above,

Thus, Flamm's paraboloid is useful for visualizing the spatial curvature of the Schwarzschild metric. It should not, however, be confused with a gravity well. No ordinary (massive or massless) particle can have a worldline lying on the paraboloid, since all distances on it are spacelike (this is a cross-section at one moment of time, so all particles moving across it must have infinite velocity). Even a tachyon would not move along the path that one might naively expect from a "rubber sheet" analogy: in particular, if the dimple is drawn pointing upward rather than downward, the tachyon's path still curves toward the central mass, not away. See the gravity well article for more information.

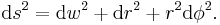

Flamm's paraboloid may be derived as follows. The Euclidean metric in the cylindrical coordinates (r, φ, w) is written

Letting the surface be described by the function  , the Euclidean metric can be written as

, the Euclidean metric can be written as

Comparing this with the Schwarzschild metric in the equatorial plane (θ = π/2) at a fixed time (t = constant, dt = 0)

yields an integral expression for w(r):

whose solution is Flamm's paraboloid.

Orbital motion

A particle orbiting in the Schwarzschild metric can have a stable circular orbit with  . Circular orbits with

. Circular orbits with  between

between  and

and  are unstable, and no circular orbits exist for

are unstable, and no circular orbits exist for  . The circular orbit of minimum radius

. The circular orbit of minimum radius  corresponds to an orbital velocity approaching the speed of light. It is possible for a particle to have a constant value of

corresponds to an orbital velocity approaching the speed of light. It is possible for a particle to have a constant value of  between

between  and

and  , but only if some force acts to keep it there.

, but only if some force acts to keep it there.

Noncircular orbits, such as Mercury's, dwell longer at small radii than would be expected classically. This can be seen as a less extreme version of the more dramatic case in which a particle passes through the event horizon and dwells inside it forever. Intermediate between the case of Mercury and the case of an object falling past the event horizon, there are exotic possibilities such as "knife-edge" orbits, in which the satellite can be made to execute an arbitrarily large number of nearly circular orbits, after which it flies back outward.

Symmetries

The group of isometries of the Schwarzschild metric is the subgroup of the ten-dimensional Poincaré group which takes the time axis (trajectory of the star) to itself. It omits the spatial translations (three dimensions) and boosts (three dimensions). It retains the time translations (one dimension) and rotations (three dimensions). Thus it has four dimensions. Like the Poincaré group, it has four connected components: the component of the identity; the time reversed component; the spatial inversion component; and the component which is both time reversed and spatially inverted.

Quotes

"Es ist immer angenehm, über strenge Lösungen einfacher Form zu verfügen." (It is always pleasant to have exact solutions in simple form at your disposal.) – Karl Schwarzschild, 1916.

See also

- Deriving the Schwarzschild solution

- Reissner–Nordström metric (charged, non-rotating solution)

- Kerr metric (uncharged, rotating solution)

- Kerr–Newman metric (charged, rotating solution)

- BKL singularity (interior solution)

- Black hole, a general review

- Schwarzschild coordinates

- Kruskal–Szekeres coordinates

- Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates

- Gullstrand–Painlevé coordinates

- Lemaitre coordinates (Schwarzschild solution in synchronous coordinates)

- Frame fields in general relativity (Lemaître observers in the Schwarzschild vacuum)

Notes

- ^ a b Schwarzschild, K. (1916). "Über das Gravitationsfeld eines Massenpunktes nach der Einsteinschen Theorie". Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 7: 189–196. http://www.archive.org/stream/sitzungsberichte1916deutsch#page/188/mode/2up. for an English translation see, arXiv:physics/9905030.

- ^ http://www.wbabin.net/eeuro/vankov.pdf – Einstein’s paper and Schwarzschild’s letter

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Karl Schwarzschild", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Schwarzschild.html.

- ^ Droste, J. (1915). "On the field of a single centre in Einstein's theory of gravitation". Koninklijke Nederlandsche Akademie van Wetenschappen Proceedings 17 (3): 998–1011.

- ^ Kox, A.J. (1992). "General Relativity in the Netherlands:1915-1920". Studies in the history of general relativity: based on the proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on the History of General Relativity, Luminy, France, 1988. Birkhäuser. p. 41. ISBN 9780817634797. http://books.google.nl/books?id=vDHCF_3vIhUC&lpg=PA39.

- ^ a b c Earman, J. (1999). "The Penrose-Hawking singularity theorems: History and Implications". In Goenner, H.. The expanding worlds of general relativity. Birkäuser. ISBN 9780817640606. http://books.google.com/books?id=5mGZno8CvnQC&pg=PA236.

- ^ Synge, J.L.. "The gravitational field of a particle". Proc.Roy.Irish Acad.(Sect.A) 53.

- ^ Kruskal, M.D. ("1960"). "Maximal extension of Schwarzschild metric". Phys.Rev. 119: "1743–1745". doi:"10.1103/PhysRev.119.1743".

- ^ Landau 1975.

- ^ Ehlers, J. (1997). "Examples of Newtonian limits of relativistic spacetimes". Classical and Quantum Gravity 14: A119–A126. Bibcode 1997CQGra..14A.119E. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/14/1A/010

- ^ RM Tennent, ed (1971). Science Data Book. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd. ISBN 0 05 002487 6.

- ^ Hughston, L.P.; Tod, K.P. (1990). An introduction to general relativity. Cambridge University Press. Chapter 19. ISBN 9780521339438. http://books.google.com/books?id=2q5Rdjn0qfgC&lpg=PA126.

- ^ a b A S Eddington, "The Mathematical Theory of Relativity", 2nd edition 1924 (Cambridge University press), at sec. 43, p.93. (In the formulae taken from the Eddington source, symbol usage has been adapted to the conventions used in the main section above.)

- ^ H. A. Buchdahl, "Isotropic coordinates and Schwarzschild metric", International Journal of Theoretical Physics, Vol.24 (1985) pp. 731–739.

References

- Schwarzschild, K. (1916). Über das Gravitationsfeld eines Massenpunktes nach der Einstein'schen Theorie. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1, 189–196.

- Schwarzschild, K. (1916). Über das Gravitationsfeld einer Kugel aus inkompressibler Flüssigkeit. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1, 424-?.

- Flamm, L (1916). "Beiträge zur Einstein'schen Gravitationstheorie". Physikalische Zeitschrift 17: 448–?.

- Ronald Adler, Maurice Bazin, Menahem Schiffer, Introduction to General Relativity (Second Edition), (1975) McGraw-Hill New York; ISBN 0-07-000423-4. See chapter 6.

- Lev Davidovich Landau and Evgeny Mikhailovich Lifshitz, The Classical Theory of Fields, Fourth Revised English Edition, Course of Theoretical Physics, Volume 2, (1951) Pergamon Press, Oxford; ISBN 0-08-025072-6. See chapter 12.

- Charles W. Misner, Kip S. Thorne, John Archibald Wheeler, Gravitation, (1970) W.H. Freeman, New York; ISBN 0-7167-0344-0. See chapters 31 and 32.

- Steven Weinberg, Gravitation and Cosmology: Principles and Applications of the General Theory of Relativity, (1972) John Wiley & Sons, New York; ISBN 0-471-92567-5. See chapter 8.

- Taylor, Edwin F.; Wheeler, John Archibald (2000), Exploring Black Holes: Introduction to General Relativity, Addison Wesley, ISBN 0-201-38423-X

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\mathrm{d}s^2 = \left[ 1 %2B \left(\frac{\mathrm{d}w}{\mathrm{d}r}\right)^2 \right] \mathrm{d}r^2 %2B r^2\mathrm{d}\phi^2,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a6114eda877b6f7190378e7cdce25877.png)